orthodontic profile andrew francis jackson

by Paul V. Reid, Bryn Mawr, PA

ANDREW FRANCIS JACKSON died in retirement in April, 1968, after a lifetime in dentistry which included more than 40 years in the exclusive practice of orthodontics and 15 years in general practice prior to that. He was known primarily as a clinician, yet he was a prolific writer and lecturer. He served a short term as a formal teacher when he headed the Orthodontic Department at Temple University from 1947 to 1949, but as a preceptor he had students throughout his years of practice. His career was anything but meteoric. His more than twenty-five published articles were evenly distributed over the years from 1927 to 1960. His first major paper was read at the annual session of the American Society of Orthodontists in 1927, his last was read before the Pacific Coast Society of Orthodontists in Santa Barbara, California, in 1958. This 30 year span of popularity bears eloquent testimony to the value of his contributions to orthodontics. The highest tribute that his specialty can confer will come to him posthumously in May of this year with the conferring of the Albert H. Ketcham Memorial Award for 1964.

Dr. Jackson was born in Concepción, Chile, on Feb. 21, 1880, of Scottish and American parents. After completing his early education in American schools in Concepción and Santiago, he decided in 1901 to come to the United States and enter the School of Dentistry at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. This was no small decision to make, involving as it did a month-long trip by tramp steamer to a new country. He graduated in 1904 and entered practice, first in Camden, New Jersey, and then in downtown Philadelphia. He was also a demonstrator in operative dentistry at the University of Pennsylvania Dental School from 1906 to 1908.

In 1914, Dr. William G. Law, a founder and first president of the European Orthodontic Society, visited Philadelphia, and it was through meeting him that Dr. Jackson became interested in orthodontics. Dr. Law helped him to treat a few cases, gave him personal instruction, and instilled in him an enthusiasm which led him to limit his practice to the specialty in 1919.

In 1911 Dr. Jackson married Elenita Allis, who also had been born in Chile of American parents. They settled in the small Quaker community of suburban Swarthmore, a college town of considerable beauty, where they reared their daughter, Helen, and their two sons, John and James. John, the elder of the two sons, studied dentistry and has practiced in Ardmore, Pennsylvania, ever since completing a preceptorship with his father. Tragedy struck the family when James, the second son, died of leukemia while a predental student. Mrs. Jackson died in 1951. In 1954 Dr. Jackson married Mrs. A. J. Fernandez, a widow and long-time friend, who now survives him.

Because of his early life in Chile, Dr. Jackson always maintained an interest in Pan-American affairs and was at one time president of the Philadelphia Pan-American Association. Throughout the years of his practice many orthodontists from Latin American countries visited his office. Because of his facility with the Spanish language, Dr. Jackson put his visitors at ease and it was not unusual for him to lapse from English into Spanish and back again in the middle of a sentence when conversing with them. In 1947 he toured South America and gave eleven lectures in Argentina, Uruguay, Chile, and Peru. He was equally well known in Europe, where he attended and often participated in the programs of many orthodontic meetings. Notable was the honor paid him in 1948 when he was invited to read one of the Tomes Lectures at the Royal College of Surgeons of London and was made a Fellow in Dentistry by that body.

If ever it can be said that a man "lived his profession,'' that statement would apply to Dr. Jackson. At work or at play, orthodontics was seldom out of his thoughts. On nights and weekends, when he was at home, he wrote. As he strolled the fairways of his Rolling Green Golf Club, where he played regularly, thoughts of the office ruined his concentration and scores but not his enjoyment of the game. In his later years he kept paper and pencil at his bedside, and many a weighty paper was first scribbled in the middle of the night while the thought was fresh in his mind. Free time in the office meant time to "play," as he termed it, with such side lines as photography. In 1955 he suffered a mild stroke which led to his virtual retirement 3 years later. This lasted for only 2 months, however, after which he reopened his office. If the stroke impaired his physical activities at all, it was evidenced only in the delegation of slightly more responsibility to his associate, and Dr. Jackson himself reveled in the extra time this left him to indulge in his favorite pastime — corresponding with his many friends about the country on any and all subjects orthodontic. A letter from “Andy,” as he was known to most, was often a masterful commentary on the current orthodontic scene. In 1962 he actually did retire, and then he pursued his correspondence more vigorously than ever.

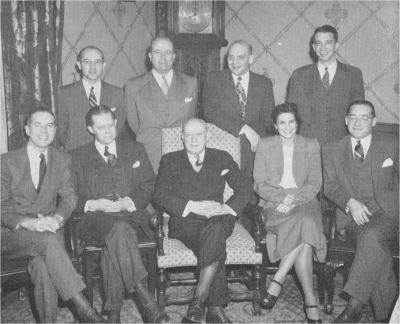

Dr. Jackson and his preceptees at a dinner at the Philadelphia Union League Club, circa 1949. First row, left to right: Paul V. Reid, Charles H. Patton, Dr. Jackson, Elizabeth Kassab, and Emil O. Rosenast. Back row: John Z. Mackenson, John M. Jackson, Aubrey P. Sager, and C. Weber Volckmer.

As he neared the end of his life, he was mercifully spared any lingering illness. Only days before his death he attended the monthly meeting of the select Stomatological Club of Philadelphia and was eagerly looking forward to the imminent meeting of the American Association of Orthodontists in Miami Beach. His was a full and devoted life dedicated to his profession.

Dr. Jackson played golf, but golf was not his main hobby. As a boy he learned to ride and in later years he took up oil painting, which he did well, but neither riding nor painting occupied a place important enough in his life to be considered a real hobby. He did, however, have a second love, which at one period in his life almost superseded his profession. He was active in the little theater movement, particularly in the Players Club of Swarthmore but was also a member of the Philadelphia Plays and Players. It was the former, though, to which he devoted most of his attention. The Players Club hardly seemed an amateur organization. It had its own modern theater which was complete in every respect, and its membership provided an ample supply of talent in both acting and directing. Dr. Jackson served in each of these capacities for many years and was once the Club's president. He knew that the secret of success in amateur shows was either a story so good as to be actor proof or, in the case of a more subtle drawing room comedy, a cast perfectly rehearsed with attention to the timing of a sentence and the inflection of a word. As an actor, he bore a striking physical resemblance to the famous Sir Cedric Hardwicke and once played the role of Canon Skerritt in "Shadow and Substance," a role played on Broadway by this fine English actor. During the week when a show was being given nightly, Dr. Jackson's practice for that period took second place in his life.

It is hardly necessary to list the contributions of one who receives the many honors, culminating in selection as a Ketcham Award nominee, which have come to Dr. Jackson. To do so in the case of a contemporary so well known and respected by colleagues around the world seems superfluous, and yet these honors should be recorded. One would have to associate Dr. Jackson primarily with the labiolingual technique. At a time when there was less emphasis on philosophies of treatment and when fewer appliances were available, he added versatility to the labial arch by the addition of an endless variety of band attachments and auxiliary springs. He devised a unique lingual attachment which simplified the direct fabrication of lingual arches and particularly of a fixed bite plane which he advocated primarily for removing vertical interferences. It is interesting to note that, aside from Crozat removable appliances and Hawley retainers, all of the appliances that he used were made directly in the mouth. It would be decidedly misleading, however, to say that he used only one technique. The twin arch, which he adopted enthusiastically in 1938, and the Crozat appliance, which at one time almost superseded all of his fixed appliances, occupied important places in his therapy. While he never used a multibanded technique as such, many of his appliance combinations came close to constituting one.

His major contribution is contained in the philosophy expressed in his writings. This he based on two "inevitable and inescapable biologic laws":

1. The infinite variations of human organisms and the uniqueness of the individual.

2. All vital processes proceed to their objectives in a series of correlated steps, each dependent on the other, but none of them quite predictable.

In article after article he stressed that an understanding and acceptance of the first of these laws is a requisite for successful practice. In a paper entitled "Orthodontic Perspective" (Am. J. Orthodontics, May, 1956), he stated:

The main difference between men and their accomplishments as enduring contributions to progress is a matter of perspective - the ability to take the big view, to see things in their true relation to a broad and comprehensive whole, and to resolve a problem to a single mental picture. This is a very rare gift and something quite apart from mere education.

At the time of his death, Dr. Jackson had a book in manuscript form and was negotiating for its publication. The following, from the preface to this work, shows what a comprehensive task he had undertaken:

ORTHODONTICS AND ORTHODONTISTS

INTRODUCTION

(CONCEPT)

Chapter l:

Orthodontics and Orthodontists.

Chapter 2:

A Simple, Understandable Pattern of Orthodontic Diagnosis and Treatment Applicable to All Cases.

Chapter 3: Orthodontic Growing Pains.

Chapter 4:

The Art of Orthodontic Practice

Chapter 5:

Open-Bite.

Chapter 6:

Excerpts From Other Papers.

Chapter 7:

The Nature and Place of Mechanical Appliances in Orthodontic Treatment.

Chapter 8:

Some Fixed Appliance Technique.

Chapter 9:

Office Management and Associates.

Chapter 10:

Personal Notes

No account of Dr. Jackson's career would be complete without mention of his faithful secretary, Mr. Frank Dunham, and his long-time office assistant, Miss Helen Vickers. Both were with him for more than 30 years and served him loyally to the end. They became part of his office and, as such, part of his life.

Andrew Francis Jackson was truly a great pioneer. He was outspoken and, to paraphrase the title of one of his papers, he loved to separate fact from fiction and fallacy. He had the courage of his convictions and expressed them freely. He loved orthodontics and opposed anything which he thought might jeopardize its future. His writings constitute a valuable heritage and will undoubtedly retain a sense of freshness over the years. They could very well be required reading for all graduate students. Finally, he gave to orthodontics more than it could possibly give him.

A PARTIAL LIST OF DR. JACKSON’S PUBLICATIONS

The Labial Auxiliary Spring, INT. J. ORTHODONTIA 15: 33-41, January, 1929.

The Interrelation of Causes, Factors and Treatment in Orthodontia, INT. J. ORTHODONTIA 16: 602-614, June, 1930.

The Nature and Place of Mechanical Interference in Orthodontic Treatment, Dental Cosmos, 73: 949-960, 1084-1094, 1162-1171, October, November, and December, 1931.

Correlation of Concept and Treatment in Orthodontia, J. A. M. A. 19: 1161-1175, July, 1932.

Facts, Fictions and Fallacies in Orthodontia, INT. J. ORTHODONTIA. 23: 1073-1095, November, 1937.

Orthodontic Sense, J. Am. Dent. A. 26: 1152-1162, July, 1939.

A Case of Deep Overbite Showing the Principle and Application of the Removable Bite Plane in Treatment, AM. J. ORTHODONTICS & ORAL SURG. 25: 745-750, August, 1939.

Orthodontic Objectives, AM. J. ORTHODONTICS & ORAL SURG. 28: 486-512, August, 1942.

Orthodontics - Its Nature and Objectives, D. Record of London, December, 1947.

The Art of Orthodontic Practice, AM. J. ORTHODONTICS 34: 383-412, May, 1948; Brit. D. Digest, August, 1948.

Orthodontics and Orthodontists, AM. J. ORTHODONTICS 36: 109-120, February, 1950.

Orthodontic "Growing Pains," AM. J. ORTHODONTICS 38: 486-505, July, 1952.

The Nature and Place of Removable Appliances in Orthodontic Treatment, AM. J. ORTHODONTICS 39: 818-835, November, 1953.

Orthodontic Perspective, AM. J. ORTHODONTICS 42: 363-380, May, 1956.

The Science, Philosophy, and Art of Orthodontic Practice, AM. J. ORTHODONTICS 44: 764-791, 839-863, October and November, 1958.

Extraction in Orthodontic Treatment; To Extract or Not to Extract - That Is the Question, D. Clin. North America, pp. 795-800, November, 1960.